Mission-Driven Metrics: A Framework for Assessing Startups Targeting National Security

How does our venture capital firm assess startups selling to national security customers?

I’m often asked: “How does your venture capital firm evaluate startups that sell (or are trying to sell) into the US Department of Defense (DoD)?” Unlike evaluating more traditional startups that rely on well studied business models like Software-as-a-Service (SaaS), evaluating startups that sell to the DoD is less straightforward. There is no “Rule of 40” equivalent for DoD revenue – it can be hard to track daily or monthly active users for products deployed on classified networks or systems that will only be regularly used during an active conflict (but are nonetheless crucial for deterrence). DoD contracts tend to be large and lumpy; a startup may have no meaningful DoD revenue for its first five years, and then finally get on a program of record worth hundreds of millions of dollars. There are often no clean ways to measure traditional SaaS metrics like annual recurring revenue (ARR), churn, customer acquisition cost (CAC), or customer lifetime value (CLV).

DoD sales cycles tend to be much longer than commercial ones, and startups may receive several different kinds of grant funding – some of which have the potential to lead to production contracts, most of which may not. Often, selling to DoD requires significant custom non-recurring engineering (NRE) work. Surprisingly (or maybe not), until recently, the DoD did not have a prescriptive pathway to buy standalone software outside of hardware. In other words, software was treated as an indefinite license tied to a larger system, and adoption of the newly established “Software Acquisitions Pathway” remains nascent. Despite some of these challenges, one benefit of working with the government is its willingness to award non-dilutive research and development (R&D) funding to help build out technology that may take years to build. Additionally, the DoD has access to test ranges available for testing capabilities that may be illegal in traditional regulated environments.

Over the past year or so, I’ve met hundreds of startups building technology that will support the national security of the US and its allies, many of which actively sell to DoD (or hope to in the future). My colleagues have met many more startups during their years as investors, entrepreneurs, DoD operators, and government acquisition leaders. In speaking with these companies, my team has developed a framework to evaluate startups in this space. I asked my colleague David Rothzeid to co-author this piece with me to help explain how we evaluate startups selling to DoD. David worked as an acquisitions officer in the US Air Force, with stints at Special Operations Command, and led acquisitions at Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) for several years, where he helped numerous startups sell cutting edge technology to the DoD.

At the end of the day, evaluating startups is not rocket science, even when they are trying to sell into the DoD. We evaluate three primary areas: 1) Team, 2) Market, and 3) Technology – in that order.

Team

The most important element of any early stage startup is its leadership team. It is critical for the leadership team to have the experience, grit, humility, work ethic, network, sales gene, technical chops, and hiring ability needed to execute on the vision they’ve outlined.

There are easier ways to make money than building technology products for the DoD – founders need to deeply care about making a difference for the national security of the US and its allies. As others have detailed at length, all startups are hard, but selling cutting edge technology into the DoD as a startup is especially hard. As Vannevar Labs CEO Brett Granberg writes, “Inventing products in the defense space ain’t easy: user problems are opaque, getting approval to test your product with users can take months, and you don’t really know if someone will pay for your thing until you’ve battled the bureaucracy for 6–12 months.” In order for a startup to have success selling to DoD, it is critical that the startups’ founders have next level persistence, energy, vision, and passion.

We typically look for founders with hands on experience working with national security customers, either through serving in the military, working as a civilian in the DoD or intelligence community (IC), working for a prime contractor, working at a national lab, conducting academic research with DoD grant money, or working for a startup actively deploying technology to national security customers. Founders with past experience working with national security customers have a head start in understanding what they will need to do to move quickly to onboard DoD customers – many already have security clearances that allow them to work with classified data and problem sets, relationships with acquisitions authorities who can help them navigate the acquisitions process, and an understanding of the technical requirements for technology sold to DoD. Working across the national security ecosystem is confusing to the uninitiated. Between the organizational structures and idiosyncratic lexicon, highly reliant on acronyms, penetrating this marketplace is challenging for even the most seasoned operators.

While national security acquisition and deployment experience is valuable, it’s not a requirement. The best founders are driven by innovation, passion, resilience, persistence, and a deep commitment to their customers, with the ability to learn quickly. We've seen founders without prior defense experience build and deliver critical solutions the DoD urgently needs.

One of the most important qualities we seek, regardless of background, is the founding team's customer obsession and empathy. Founders must engage directly with real end users – not just those in the DoD's many innovation hubs – and identify a genuine pain point that these users are eager to resolve.1 Navigating the acquisition process is tough, so solving a high-priority problem for end users who are willing to fight for a solution is essential. The issue must be significant enough that customers will push through bureaucracy to address it. Founders must inspire that level of commitment and be ready to stand alongside their customers in the fight.

To gauge a founding team's familiarity with selling to the DoD, we’ve developed a set of questions that help us assess whether they've done their basic homework on their DoD go-to-market strategy. We certainly don’t expect early-stage founders to have perfect answers to these questions, and we understand that responses will likely evolve as startups pivot and gain deeper customer insights. However, any founder aiming to sell to the DoD should at least have a general understanding of how they might approach these questions:

Who is the end user for this product and how many end users are there?

Which program executive office(s) support the users?

Do you have an empowered champion inside the system who will fight bureaucracy to see it adopted?

If you have an SBIR/STTR or other early stage prototype project, what is your plan to transition this product into a production contract?

What kinds of accreditations will you need to deploy this software? Do you have a sponsoring body?

Are there existing programs in execution related to your capability? Will you need to partner with an existing performer (likely a defense prime contractor) or unseat them?

Is your capability and ability to sell related to other ongoing efforts i.e. are you dependent on other projects?

Tell us about the end users / customers you’ve spoken with? What surprised you about those interactions? What confirmed your conviction that this is a top priority problem to solve?

Market

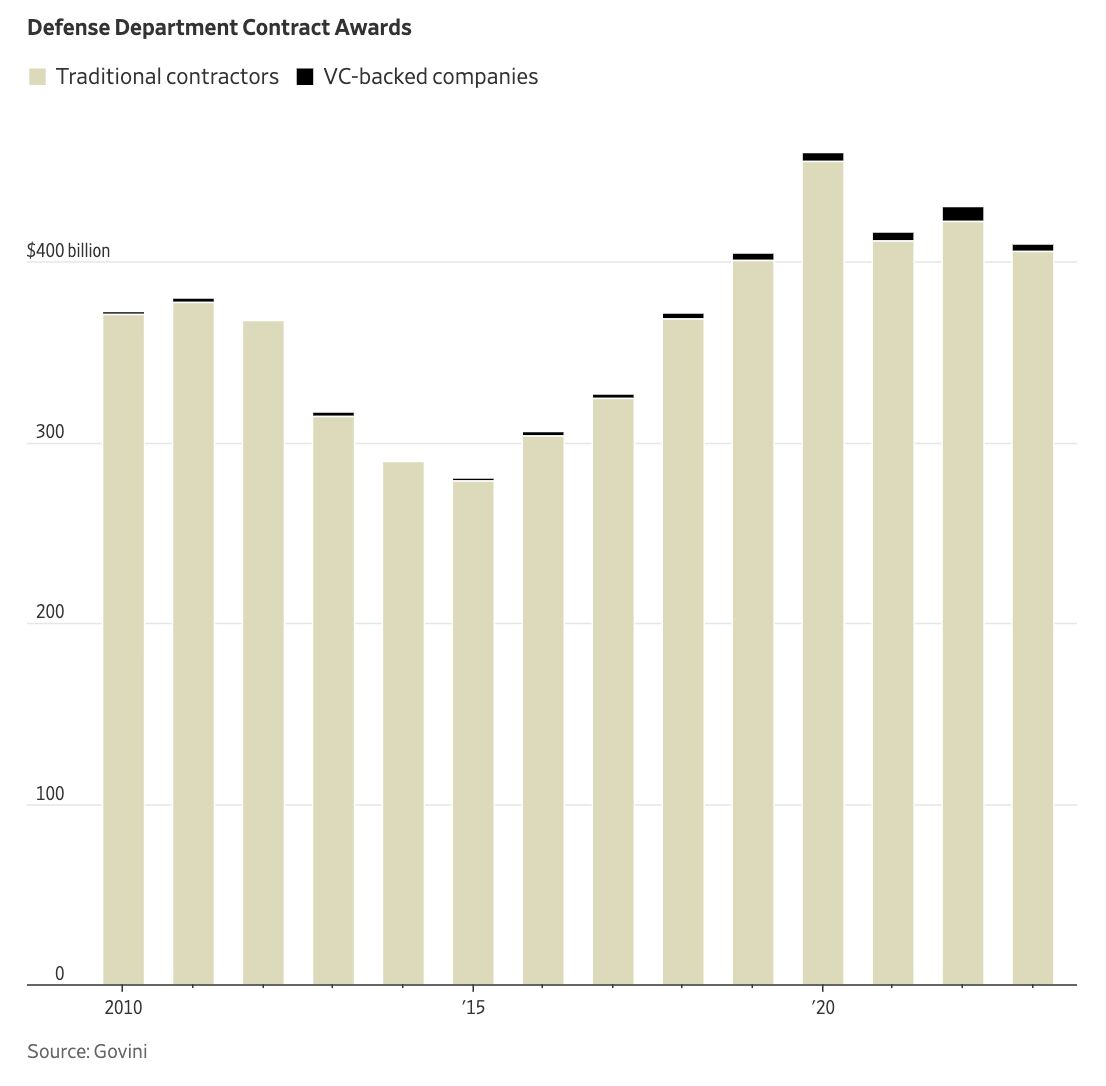

While it is crucial for a startup to have a great team and product, it is essential that they are tackling a large enough market to produce outsized returns. It’s true that the DoD has a massive budget – the DoD’s 2025 budget request is $849.8B. However, just a fraction of this budget goes to actually buying and sustaining technology. Of the $849.8B requested for 2025, $143.2B is requested for research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E) and $167.5B (only 20%) is requested for procurement. An even smaller fraction of this budget actually goes to VC-backed startups (most goes to traditional prime contractors and government technology services providers).

It’s important for startups to have a realistic understanding of their DoD revenue potential and how they can achieve market penetration. The DoD acquisition system is a maze of terminology and opportunities. For this section we will outline the myriad of R&D funding sources, contractual pathways, and processes by which a company can achieve a thing called a program of record (PoR). Finally, we will sprinkle in some nuggets for how we assess a startups traction when evaluating their progress for a potential investment.

R&D funding source opportunities:

When we evaluate startups’ DoD contracts, we look for contracts addressing a priority problem for end users that have the potential to convert to production contracts. It is important to understand the difference between R&D and production contracts. It is not overly difficult for startups to land small “innovation” grants and R&D contracts like Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) program, or even DARPA projects. However, most of these small R&D contracts do not equate to ongoing revenue or production contracts, and as such do not have the potential to convert to large production contracts that actually field technology to end users.

Arguably the SBIR and STTR programs are the most popular DoD funding sources for early stage startups. In fact, the majority of startups we meet have typically landed a handful of SBIRs or SSTRs.2 The DoD SBIR program awards ~$2B in grants/awards which can be a great way for startups to get some early, non-dilutive funding and initial DoD touchpoints. As investors, the value of the SBIR is generally positive, but real value comes with nuance. For the uninitiated, there are three phases of SBIRs – Phase I SBIRs are relatively low lift and only require the startup to produce a white paper on a particular technology. For Phase II SBIRs, the funding amount can be anywhere from $500K to $1.5M and with it an increase in expected deliverables. However, the real utility is not the quantity in funding, but rather the quality of your Phase II sponsor, commonly highlighted in the statement of work as the Technical Point of Contact (TPOC). A high quality TPOC is someone who can be your advocate and champion helping your startup parlay that small Phase II SBIR into a much larger, follow-on production contract. The real power of the SBIR program is its ability to enable a company who successfully completes a Phase II SBIR to be awarded a non-competitive, sole source Phase III SBIR.3

A more recent wrinkle elevating the value of SBIRs is due to the ingenuity inside the Department of the Air Force’s (DAF) and Department of the Army in creating the TACFI/STRATFI and Catalyst programs respectively. TACFI/STRATFI programs are based off of Phase II SBIR awards, encourage use of matching funds, and are typically aligned to priority problems of the United States Air Force and Space Force. These programs use SBIR dollars to match private investment dollars or other government investment dollars at a 1:1 (TACFI) or 1:2 (STRATFI) ratio. The STRATFI can garner $15M in non-dilutive R&D funding from the SBIR pot of funding. Similarly, the Catalyst program is also based off of the Army’s SBIR program, encourages use of matching funds, and is typically aligned to priority problems of the United States Army. Catalyst has a 2:1:1 funding ratio for SBIR dollars, with up to $7M available from the SBIR pot of funding, and allows matching funding to come from other DoD sources, defense primes, or other 3rd party capital sources.

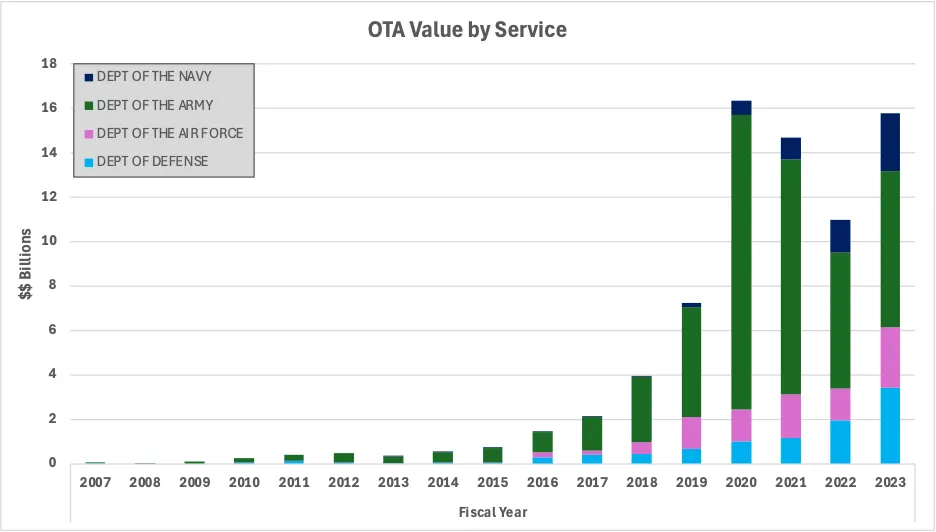

As investors who care deeply about the National Security landscape, we are major advocates of the services and government writ large taking advantage of matching programs like TACFI/STRATFI and Catalyst. More important is the signal to us as investors that the start-up has achieved product-market fit with their end customer with these valuable R&D programs. All that being said, SBIR is only ~$2B of the $134B RDT&E portion of the DoD’s budget. Truthfully, most of this funding goes to fund DoD lab activities for basic research. The portion available for industry, typically awarded through a solicitation mechanism called a broad agency announcements (BAAs) can be found on SAM.gov. However, the vast majority of these awards are either for service work or tied to existing programs of records with existing performers. However, there is a growing portion of R&D activities tied to a contracting authority called Other Transactions. In our next section where we highlight the nuance of contracting we’ll dive deeper into where and how these underutilized, commercial friendly contract avenues appear.

Contractual Pathways:

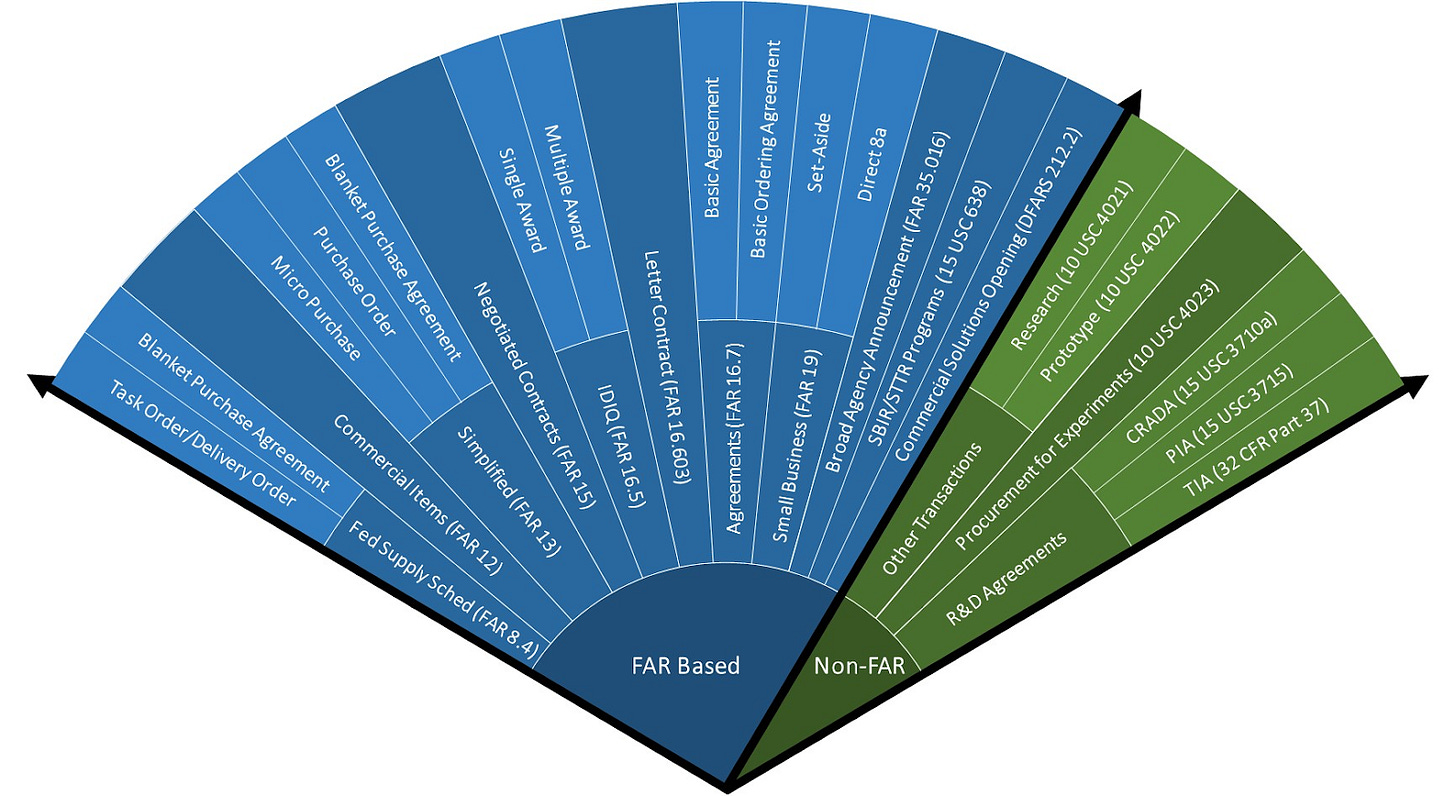

The vast majority of all DoD funding will be awarded through something called the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR). Put simply, the FAR is 3,000 pages of rules and regulations acquisition professionals must adhere to in order to ensure fairness, transparency, and competition when awarding government contracts. In truth, the FAR should provide the necessary flexibility to allow government organizations to do all kinds of novel partnerships with industry. However, in practice, the FAR has become a bit of a checklist overlord best left for awarding services contracts related to base lawn care and janitorial services.

A very common contract pathway some early stage startups may be aware of are Indefinite Deliverable, Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) contracts. IDIQ contracts are more flexible than other types of federal contracts and are commonly used for R&D projects – most other federal contracts state the exact quantities and delivery timelines for goods or services, but an IDIQ contract does not require such specifics. IDIQs can be high leverage or inconsequential, depending on the program and whether you are the sole performer or one of many. An IDIQ is essentially a “hunting license” that allows companies to sell to DoD customers, but an IDIQ typically does not actually provide revenue to a company on its own (so, a company that has “won” a $100M IDIQ may not have any actual revenue from DoD, or they may have received only a fraction of the full $100M IDIQ ceiling). Companies with an IDIQ still need to bid on and win individual delivery / task orders in order to see revenue. IDIQs often have high “ceilings” (the maximum total dollar value authorized for all task or delivery orders) – for example the USAF’s JADC2 IDIQ has a $950M ceiling – however, those contract ceilings are often divided up among many companies (the JADC2 IDIQ has dozens of competing vendors). So, it is unlikely for one company to win the full ceiling value of an IDIQ unless they are the sole performer on that IDIQ. What we as investors look for is whether any delivery / task orders have been awarded and whether the IDIQ is aligned to an existing program inside the DoD’s budget.

Another popular FAR based contract type is called the Governmentwide Acquisition Contract (GWAC). For a more mature startup they may have distribution partnerships with value added resellers to gain access for GSA4 schedule or NASA SEWP,5 two popular contracting vehicles to buy IT licenses and other managed services. For the unfamiliar, it’s not a problem, though it highlights how a good investor can help accelerate familiarity and growth for their startups.

Thus far, most of the contracting mechanisms we’ve discussed have been FAR-based contracts. However, there are also contractual pathways that are not subject to FAR rules (the green side of the fan).

Of the non-FAR based authorities, Other Transactions (OT) agreements can provide startups the best opportunity to gain meaningful traction. OT agreements are particularly interesting because of their overarching authority and level of flexibility. Essentially, if a company competes and wins an OT agreement, and it successfully completes the contractual milestones, then the company is eligible to move into a sole source production contract (similar to SBIR Phase III authority) with any representative customer who has a need for the outcomes associated with the original prototype OT award. OTs are becoming more popular by various program offices.6 Two mechanisms worth highlighting are the Defense Innovation Unit’s (DIU) Commercial Solutions Opening (CSO)7 and the plethora of DoD OT Consortiums. DIU CSOs are particularly compelling due to their high transition rates (51% as of Fiscal Year 2023), indicating that prototype efforts often evolve beyond one-off projects into sustained programs. DIU CSO awards are also extremely competitive – often 100+ companies compete for the same area of interest. Of all the DoD organizations and contractual pathways, DIU remains the gold standard because of its focus on transitioning prototype projects into production. However, with DIU’s 3.0 shift, it is likely the operating model will change so it is unclear whether DIU CSO solicitations will continue in the same manner similar to the DIU 2.0 framework. As for DoD OT Consortiums, there is less publicly available information highlighting successful transition, though it is worth noting the $250M Palantir Army Tactical Intelligence Targeting Access Node (TITAN) program came through the C5 consortium.

Programs:

In the long term, the typical focus for firms focused on the government as a major buyer are programs of record (PoR) – large, multi year contracts that appear in the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP) and for which Congress has appropriated funding or intends to (ex: the F-35 is a PoR). PoRs are somewhat mythical entities that can be hard to describe and frustrating to achieve. They are created through the DoD’s ‘Big A’ acquisition process involving the Joint Capabilities Integrated and Development System (JCIDS), which is the DoDs process for creating requirements for future programs. This document heavy process may or may not involve R&D contracts for exercises and demonstration purposes, but the goal is to take those established requirements and fight for budget in through the Planning, Programming, Budgeting and Execution (PPB&E) process. Assuming the DoD is able to reconcile its budget through the program objective memorandum (POM) process, and Congress approves that line item in the budget, the DoD can then engage in ‘little a’ acquisition which involves soliciting and competing the contract across industry for the validated requirements and budgeted line item. This whole business of establishing, budgeting, and awarding PoRs can take 5+ years. Notably, Anduril won its first PoR in just under 3 years, the fastest transition to PoR in 70 years.

Of course, we do not expect early stage startups to have PoRs, and in order to be successful, we are not even suggesting a startup needs to create and win a PoR, but they can be a good way to establish a market size, and identify customers and competitors when entering the industry base. To the DoD’s credit, it has established a few programs to help bridge this gap to help go from proof of concept or a prototype project into a structured program. The aforementioned TACFI/STRATFI and Catalyst programs can operate as a bridge, but a few years ago, through the vision of Congressman Calvert, the DoD established the “Accelerate the Procurement and Fielding of Innovative Technologies,” better known by its acronym “APFIT.”

Another way a startup can gain traction tied to programs is through subcontract teaming arrangements. The DoD generally relies on defense prime contractors to serve as system integrators, rather than performing the integration of complementary components into a cohesive system in-house. So, startups building technology that can be integrated into a broader platform may consider being a subcontractor to a prime rather than trying to win a prime contract on their own. For example, European startup Helsing has a strategic cooperation agreement with Saab, a European defense prime, to work together on large European prime defense contracts. In summer 2023 the German Ministry of Defense awarded Helsing and Saab a contract to upgrade the Eurofighter – Saab is providing a hardware sensor suite while Helsing is providing AI software to upgrade “the reconnaissance and self-protection capabilities of the Eurofighter through AI-enabled, cognitive EW capabilities.” Similarly, L3Harris (the 6th largest US defense contractor) has positioned itself as a “Trusted Disruptor” in the US defense space and, as such, prioritizes working with startups on DoD projects. For example, L3Harris has a partnership with autonomous surface vessel (ASV) startup Seasats to outfit Seasats’ ASVs with L3Harris networking payloads.

Final thoughts on Market:

The above serves as a standard jumping off point for how we assess start-ups selling into the government and opportunities a startup might consider pursuing to gain traction. Depending on the stage and maturity of the start-up, we may look deeper at the type of funding received, commonly referred to as “colors of money.” A startup with established, repeatable contracts should be receiving procurement and/or operations and maintenance (O&M) funding, beyond the typical research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E) funding.

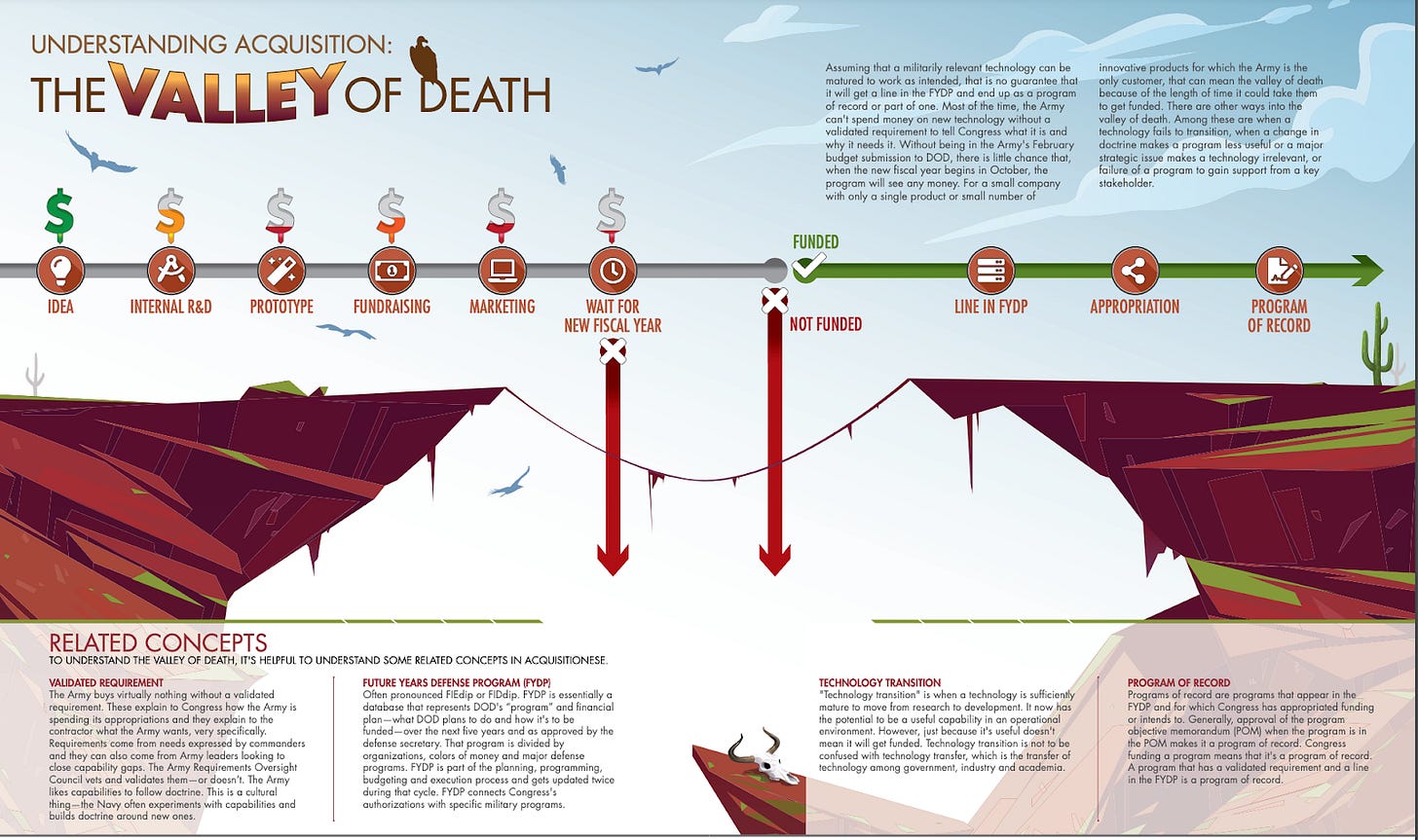

Ultimately, due to the power law nature of venture capital,8 we look for startups that have the potential to make $100M+ in annual revenue. As we’ve outlined here, selling into the DoD is difficult and time consuming. As such, we typically look for startups who will also be able to expand their total addressable market (TAM) by selling their product to non-government customers. It is extremely difficult for a startup to reach venture scale solely selling into the DoD, so we typically advise startups to develop a product that can sell into multiple industries. Selling to commercial customers can help startups scale, enable startups to get fast product feedback to iterate and improve their products, and help startups get revenue to survive the infamous “Valley of Death” between being awarded R&D contracts and transitioning to production contracts.

Technology

The final piece we evaluate for any startup looking to sell into the DoD is technology. As with any startup, we’re looking to assess if the technology is feasible to build and field in a reasonable timeline at a reasonable cost, if the unit economics make sense, if the technology is sufficiently differentiated, and if the team has the experience needed to actually build this technology.

As I’ve written about in the past, deploying technology to national security customers has its own set of technical challenges. When we assess startups’ technology, we look to ensure that the founders have an understanding of the constraints, certifications, and accreditations they will need to face to deploy their technology within the DoD. Startup founders need to make sure it is actually possible to meet the DoD’s technical constraints at a workable price point. For instance, if a startup wishes to train a large AI model on classified data, they need to have a plan of how they will actually access the GPU and compute resources they need to train on a classified network (spoiler alert: they may have real difficulties accessing these compute resources). Similarly, if a startup plans to sell drones or other hardware to the DoD, they need to be aware that the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) requires that certain hardware components like RF chips and flight controllers are designed and built in the US or some allied countries. Building NDAA-compliant hardware at a competitive price point can be a real challenge for many startups. Additionally, both software and hardware startups will need to have a plan to test and harden their technology for DoD standards – software startups will need to undergo robust security testing to acquire an ATO while hardware startups will need to ensure their hardware complies with performance requirements like MIL-SPEC and MIL-STD.

There are several tech “strategies” we have seen successfully deployed to DoD. The first includes those creating entirely new technologies for defense use, like Anduril, which pioneers systems that require significant customer education and high R&D costs but establish deep tech moats and long-term influence over requirements. These startups must navigate a fine line of convincing the DoD to change how they operate in order to take advantage of modern technology opportunities. However, this path has the benefit of establishing a unique and defensible market position, typically resulting in the aforementioned PoRs.

Another strategy involves startups improving existing DoD technologies by reducing costs, improving usability, or expanding scalability. Companies like Apex Space and Albedo Space exemplify this strategy by refining satellite technology – satellite bus manufacturing and 10cm earth observation imagery respectively. The DoD already has access to satellite bus manufacturing technology and 10cm earth observation imagery, but the current state of the art for both technologies are extremely expensive and inefficient. While these startups avoid the need for customer education, they face the challenge of displacing entrenched vendors and risk competing primarily on price, requiring strong execution and process advantages. The third strategy adapts private sector technologies for DoD use. For example, C3.AI developed data analytics products for the DoD, leveraging technology that had already demonstrated successfully in commercial applications. These startups focus on integration and execution moats rather than technical innovation, as their value lies in adapting existing tools to meet specific defense needs.

When assessing a startup’s technology, we also look to understand the competitive landscape. In particular, we try to get a sense of how the defense primes are operating in the competitive landscape. We look for startups that are developing technologies that the primes cannot or will not develop themselves. It’s hard for us to get excited about a startup that is building some exquisite, capital intensive, defense-only technology – fundamentally, this is where the primes have a considerable advantage. Instead, we look for startups building cutting edge technology, using modern practices, that the primes do not necessarily have the talent, agility, vision, or insight to build.

Further, there are certain technology areas that are extremely difficult for startups to penetrate due to classification levels. The defense primes have armies of cleared engineers who are able to work on highly classified technology. We frequently come across startups building technology that they believe is novel that, unfortunately for them, already exists in classified programs that are not publicly known (this is particularly common in space and maritime sensing, communications, electronic warfare, and computing). Even if a founder has a clearance and understands the classified space, it is difficult for startups to hire highly skilled cleared engineers – many startups end up hiring engineers without security clearances, who then need to navigate the lengthy and complex clearance process. While we do not expect founders to have perfect information in this realm, as investors this is something we think about before investing, so it is important for a founder to perform market diligence to the best of their ability in order to understand whether what they intend to build is competing with well established, classified technology.

We hope this post can help startup founders navigate the complicated world of DoD acquisitions and opaque VC decision making. If you are an early stage startup and not all of this is familiar to you, that is perfectly fine. But if you are going to be focused on selling into defense, it is important to surround yourself with investors with first hand experience in navigating this maze of DoD procurement opportunities. As always, please let us know your thoughts, and please reach out if you or anyone you know is building at the intersection of national security and technology!

For this blog we’re going to focus on SBIRs over STTRs

While the SBIR program is broken into three phases, the difference between Phase I/II and Phase III is who provides the funding. SBIR Phase I/II’s are funded through a central source, whereas Phase III funding comes from the government customer organization.

GSA = General Services Administration

SEWP = Solutions for Enterprise-Wide Procurement

For good analysis of the use of OTs over time, check out Austin Gray’s post on “OTAs, Defense Tech, & The Path To Revenue.”

For more on the history of the DIU and the DIU’s CSOs, we highly recommend the book Unit X by Raj Shah and Christopher Kirchhoff.

For those interested in learning more about the history and incentives behind venture capital, we recommend reading The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future by Sebastian Mallaby.

Note: The opinions and views expressed in this article are solely our own and do not reflect the views, policies, or position of our employer or any other organization or individual with which we are affiliated.