CDAO and Accelerating DoD AI Adoption

Adventures in data integration, CJADC2, the data mesh, and more…

In order to remain competitive, the US military must accelerate its adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) in order to improve American warfighters’ strategic and tactical advantage.1 US adversaries like Russia and China are actively integrating AI into their own military systems in order to speed up the pace of their military decision making and operations.2

Already, the Pentagon is working on more than 800 AI-related projects, and in late 2021, the DoD officially established the Chief Digital and AI Office (CDAO) to be the primary office responsible for the DoD’s AI strategy and adoption.

With Dr. Radha Plumb named to succeed Craig Martell, who has led the CDAO since its inception, now is an opportune moment to take stock of the CDAO's accomplishments and areas for improvement. Such reflection is vital for steering the CDAO towards even greater effectiveness and relevance in advancing the DoD’s AI capabilities.

This post will dive into the DoD’s CDAO to help demystify the DoD office primarily in charge of policy for the DoD’s AI adoption. What is the CDAO? What are its priorities? How did it come into being? What has the CDAO done so far? What more can and should it do?

What is the CDAO?

The CDAO was established in late 2021 as a direct report to the Deputy Secretary of Defense to integrate several existing organizations and programs.3 The CDAO officially became operational in July 2022 and is meant to be the DoD’s primary data and AI policy lead.

In November 2023, the CDAO released the DoD’s Data, Analytics, and Artificial Intelligence Adoption Strategy. The strategy emphasizes that the ultimate goal of the DoD’s data, analytics, and AI adoption is improving warfighter decision advantage, a competitive condition characterized by the following outcomes:

Battlespace awareness and understanding

Adaptive force planning and application

Fast, precise, and resilient kill chains

Resilient sustainment support

Efficient enterprise business operations

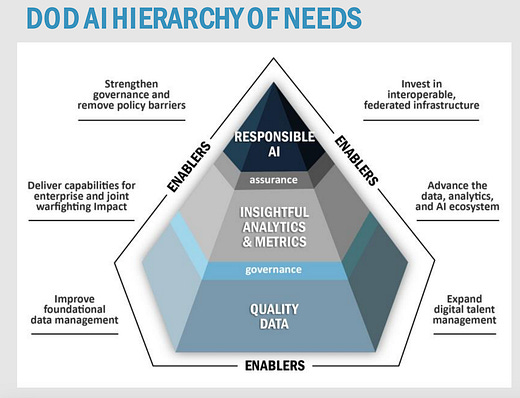

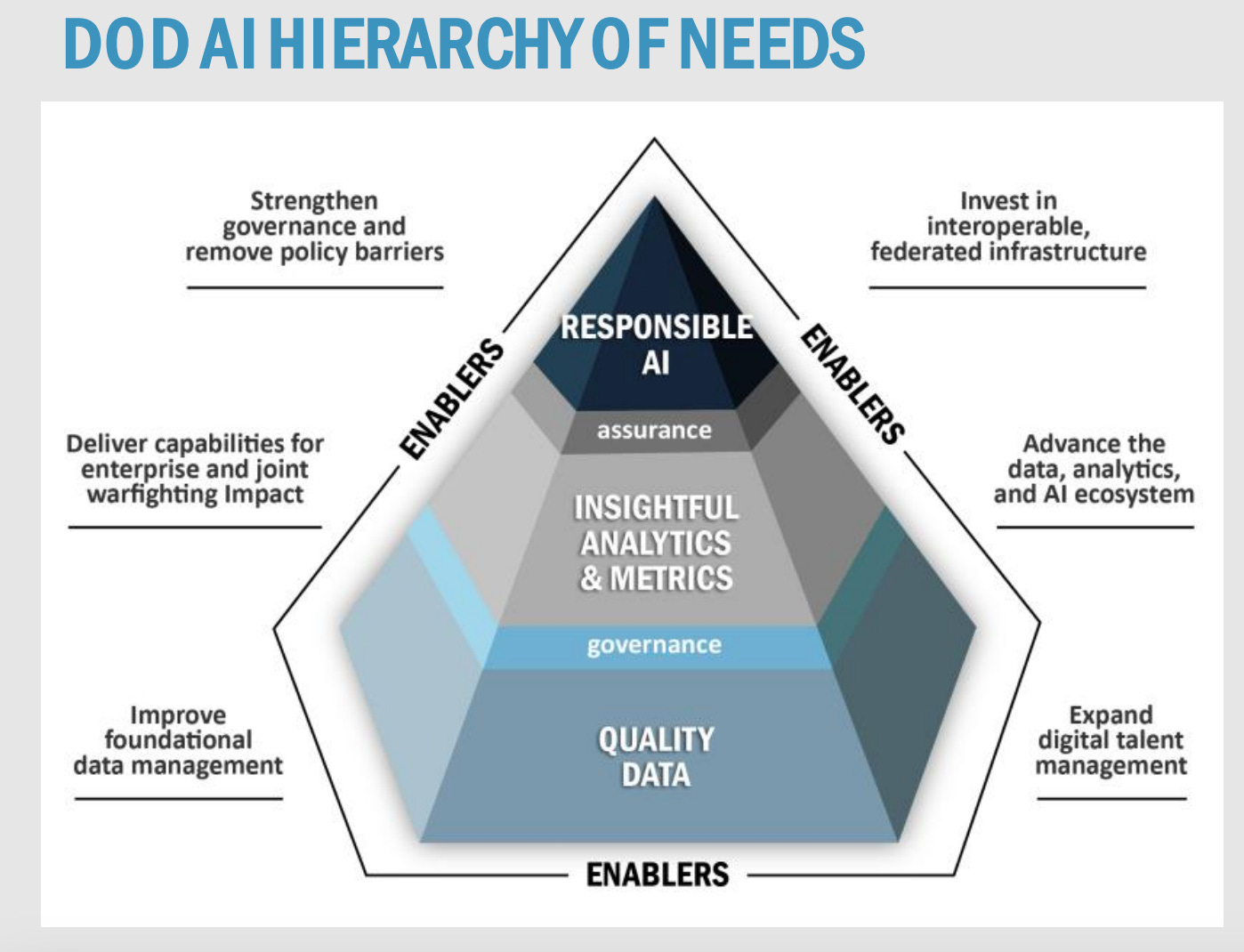

In this strategy document, the CDAO published a pyramid chart highlighting their strategic priorities for AI:

Data Integration, High Quality Data, and the Data Mesh

Notably, “high quality data” is at the very base of the pyramid. AI algorithms are only as good as the data they are trained on, so before building AI applications, Dr. Martell argues, the DoD needs to produce and organize its data. The DoD is not an organization that employs a large number of AI experts. However, what the DoD lacks in AI expertise, it makes up for with its large amount of unique data – decades worth of design and operations manuals for hardware systems, war games, geospatial intelligence, signals intelligence, human intelligence reports, cutting-edge scientific research, etc.

Currently this data is siloed, unorganized, overclassified, and difficult to find. So, Martell has outlined the DoD’s plan for a “Data Mesh” – essentially a federated data catalog that organizes all of the DoD’s data and allows AI experts to search for that data in one place (one step along the pathway to creating a DoD-wide data lake). Of course, it’s not reasonable for the DoD to move all of its data into one centralized location, but it can catalog its data and store that catalog in one place so that the AI experts can find the data to develop powerful AI-enabled tools. Once the DoD has its data organized, it can partner with tech companies to develop AI applications using the DoD’s data catalog.

The CDAO’s plan to implement one singular DoD-wide data mesh, while noble, may ultimately be unrealistic, given each individual services’ incentives to develop their own data integration platforms that best suit specific use cases. Already, individual services have started implementing their own data integration platforms that are able to bring together data from disparate sensors and sources. For example, the US Air Force (USAF) and Space Force (USSF) have developed a cloud environment known as the “Unified Data Library” (UDL) which ingests data from different sensors and standardizes the data to be used for analytics. USAF and USSF are using UDL for their Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS) and space situational awareness (SSA) programs, both part of the DoD’s overarching CJADC24 strategy, to integrate sensor data and provide warfighters with decision advantage.5 To best implement a DoD-wide data mesh, the CDAO should empower each service to develop the best data integration product for their specific mission and then set policy to enable integration between different Services’ data mesh.

It’s important to note that implementing a DoD-wide data mesh is not a silver bullet for all of the DoD’s data and AI development challenges. As those who have deployed AI in the DoD point out, the DoD does not always have the data it needs for particular AI applications. For example, as a result of the DoD’s focus on the Middle East over the past several decades during the Global War on Terror, the DoD amassed a large trove of Arabic language and Middle East focused data. However, it lacks large datasets focused on China and Mandarin language, which have become relevant as the DoD shifts its focus to deterring China as part of Great Power Competition. So, in order to train and deploy AI products focused on China, AI product developers need to curate their own datasets, as they cannot rely on the DoD to have the necessary data. Without relevant data, AI is useless (ex: you cannot create a product that translates Mandarin Chinese social media posts into English without training your AI algorithm on Mandarin language data). Curating relevant data is a key part of the AI product development process – it is impossible to extricate the value of the underlying data from the AI application itself.

Even if the DoD has the data it needs for effective AI applications, the Pentagon faces other data integration and analysis challenges. According to a Defense Innovation Board (DIB) report, data analytics and integration products for classified networks are severely lacking, significantly limiting the effectiveness of existing data analytics capabilities. Much of the DoD’s data is classified and can only be hosted on classified networks like the Secret Internet Protocol Router Network (SIPRNet) and the Joint Worldwide Intelligence Communication System (JWICS). Some companies, such as Ghostdog and Palantir, are working to improve the user experience for sharing data on classified networks, but these companies still face an uphill battle.

Furthermore, as outlined in the same DIB report, DoD data integration hits road blocks due to the DoD’s “API problem.” In the commercial, non-government world, most modern software products have easy to use application programming interfaces (APIs) that enable easy data integration between different systems.6 However, much of the software used by the DoD lacks high quality APIs, making it difficult to integrate applications developed by different vendors and leading to significant duplication of manual effort to input data from one system into another.

This lack of high quality APIs is largely a result of misaligned incentives and poorly defined requirements. Many DoD vendors are disincentivized from creating technology that easily integrates with other systems, as they fear that making it easier to integrate with competitors erodes their competitive advantage. Many DoD software vendors also feel that the data available in their platforms (that could be extracted via high quality APIs) is a key part of their product. Much of the DoD’s data is low quality and unorganized, and often the DoD does not actually have the data needed to build effective AI products. DoD AI vendors like C3.AI and Vannevar need to do a tremendous amount of work to extract, process, organize, and even procure the data needed to make their data analysis platforms work. So, if it was easy to extract the data these companies painstakingly generated, organized, and cleaned, these companies would worry that part of their intellectual property is available to a competitor.

Still, it is crucial that DoD’s technology vendors are able to easily integrate with other systems. To ensure systems are developed with data integration in mind, the CDAO should outline policy guidance that would require DoD software vendors to implement high quality APIs for their software, even if it is not ideal for vendors’ business models. Lack of easy integration has led to massive challenges for programs like the F-35. As a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report outlines, F-35 program maintenance has struggled in part because Lockheed Martin and its subcontractors are unwilling to share technical data with each other and with the services because they fear losing a competitive edge. This unwillingness to share technical data has led to meaningful delays in repairing and maintaining malfunctioning F-35 software and hardware components. Often DoD requirements do not clearly define data integration needs in part because of a lack of foresight – information systems are frequently developed to do a single job, without whole systems in mind, so data integration is not taken into account.

Beyond data integration, what else does the CDAO do?

The CDAO has done more than just outline plans for a “Data Mesh.” The CDAO manages several DoD AI products including Advana and Project Maven. Advana is a data analytics platform developed by Booz Allen and Databricks for analyzing unclassified data.7 Since taking over Advana, Advana’s user base has nearly tripled (going from 40,000 users to 110,000), lowering the barrier to entry for basic data analytics. However, Advana is not currently supported in classified networks like SIPRNet and JWICS, limiting its effectiveness to analyze some of the DoD’s most important data.

The CDAO also oversees certain segments of Project Maven, a military AI initiative that first garnered attention when it faced protests from Google employees in 2018.8 The most well-known initiative within Project Maven is a geospatial intelligence product run by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), not the CDAO, that uses computer vision to enable the DoD to identify targets from geospatial (drone and satellite) imagery.9 US military partners have deployed Project Maven’s geospatial capabilities in Ukraine for targeting use cases.10 The CDAO is responsible for Project Maven’s other initiatives which include technologies like social media analysis and “publicly available information” (PAI) analysis.

In addition to Project Maven and Advana, the CDAO has taken actions to advance AI adoption in the DoD. The CDAO has run several “Global Information Dominance Experiment” (GIDE) series to test how different technologies perform in real world scenarios relevant to CJADC2. It has also funded two AI battle labs “to design and test new capabilities with warfighters in open and competitive environments.”11 These battle labs plan to run a series of U.S. federal government-wide hackathons to explore use cases for AI in the DoD. In August 2023, the CDAO established Task Force Lima, a working group to assess use cases for generative AI in the DoD. So far, CDAO has primarily focused on applications of generative AI to backend “business operation automation” tasks (like those related to human resources, knowledge management, and logistics). For example, in an interview, CDAO AI experts discussed a DoD initiative that employs generative AI to support cybersecurity analysts and another project designed to facilitate efficient searches through DoD policies and regulations.

The CDAO’s primary contracting vehicle is Tradewinds, a $4B Other Transaction Agreement (OTA) funding vehicle that allows the DoD to accelerate the acquisition of AI capabilities to meet challenges and objectives. Tradewinds is meant to serve as “an online marketplace that allows CDAO to broadcast and manage AI opportunities to industry and interface with an ecosystem of partners and companies that can deliver AI technologies and capability.” It is also designed to interface with the DoD to understand “AI needs, problems, and challenges that have the potential to be solved by AI.” Companies who are on Tradewinds are not guaranteed to win government contracts, but the CDAO has budget to purchase capabilities through the Tradewinds contracting vehicle.12

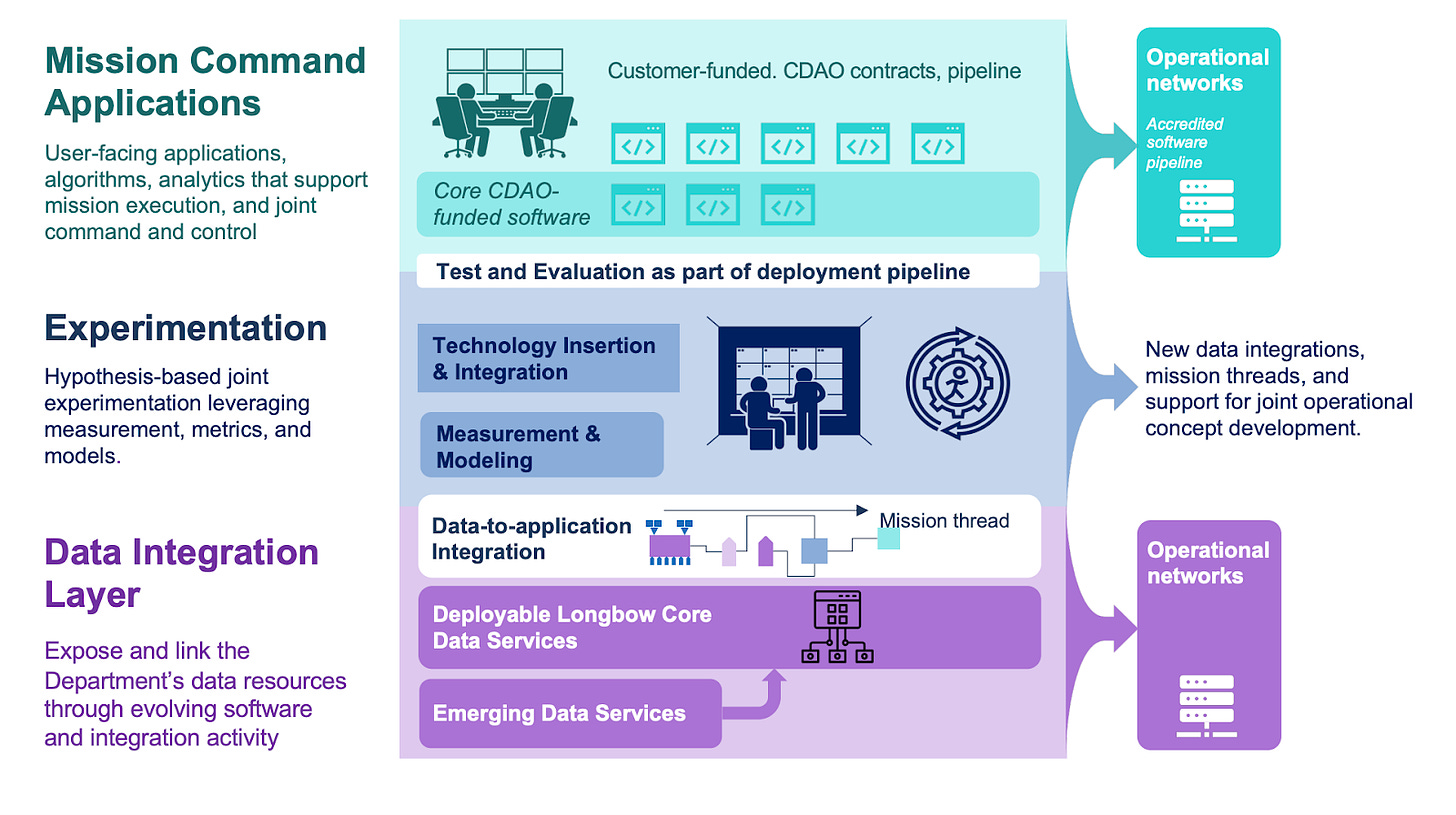

Notably, the CDAO resides within the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), whereas the majority of the DoD’s budget is allocated by the Services (Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force, and Coast Guard) through Program Executive Offices (PEOs). The Services are the primary entities responsible for equipping, training, and maintaining warfighters, so any AI product will eventually need to gain buy-in from the Services to see widespread adoption. As evidenced by a CDAO presentation on CJADC2 (one slide of which is displayed below), the CDAO hopes that the Services will purchase AI products that have been tested by the CDAO through CDAO contract vehicles like Tradewinds, but thus far, it is not clear that any Services have a desire to do so. Nevertheless, it is vital that the CDAO continue to strengthen its relationships with the Services, so that they can get a real sense of end users’ needs and set policy for AI adoption accordingly since the Services will actually buy and use AI products.

One of the CDAO’s more promising initiatives is the “Accelerating Data and AI” (ADA) initiative (whose budget was recently extended through 2029), which works to accelerate the adoption of data analytics and AI within the Combatant Commands (COCOMs)13 by embedding teams of data analytics experts within those COCOMs. These teams were modeled off of data-focused teams within SOCOM14 that were successful in enabling SOCOM’s adoption of data analytics (for example, SOCOM has successfully used data analytics for tasks like predictive maintenance for aircraft). This initiative helps directly connect data analytics experts with specific teams that could be improved by AI and data analytics. However, so far, these ADA teams have had mixed results.

Teams embedded within COCOMs led by tech-savvy leaders who identified clear tasks that could be enhanced by data analytics experienced success in accelerating the integration of data analytics and AI within their organizations. Conversely, some ADA teams faced challenges with leaders less inclined toward enhancing their data analytics prowess, which impeded these teams' effectiveness in fostering technological adoption. ADA teams were most successful when leaders tasked them with specific problems that could be improved by data analytics, such as tasks related to financial management, logistics and supply chain, workforce and personnel, and global force management.15 In order to improve the effectiveness of this initiative, the CDAO should clearly define ADA teams’ responsibilities. Additionally, ADA teams should act as a conduit between the CDAO and the COCOMs in order to connect end users with relevant technology.

Further, in early 2022, the Pentagon directed the COCOMs to appoint Chief Data Officers16 to help the COCOMs better understand and use their data. Similar to the ADA teams, COCOM Chief Data Officers have had mixed results, in part due to their lack of resources and lack of clear authorities. Again, CDAO should clearly define the COCOMs’ data leader authorities and provide them with resources to effectively lead data-driven initiatives. Additionally, CDAO should leverage these data chiefs as intermediaries between the CDAO and the COCOMs. While the COCOMs do not control as much budget as the Services, they are responsible for planning specific mission sets and have intimate understanding of the problems faced by warfighters that could be improved through AI adoption.

Finally, CDAO has put significant emphasis on developing its “Responsible AI toolkit” which “provides a centralized process that identifies, tracks, and improves alignment of AI projects to RAI best practices and the DoD AI Ethical Principles, while capitalizing on opportunities for innovation.” This toolkit includes initiatives like the “SHIELD Assessment” and the “DAGR Risk Guide” which help manage AI product life cycles and assess the risk of adopting AI for different applications.

There is no doubt that the DoD must be responsible in its adoption of AI to be successful. That being said, when developing AI applications, the DoD should not be focused on perfection, but rather should assess whether integrating AI into a particular task offers a net benefit over not using it at all. Particularly for tasks that are not kinetic or mission critical, the Department should prioritize implementing solutions that, while not flawless, represent an improvement over existing systems. For example, as a CDAO data scientist mentioned in an interview, AI could be used to help the DoD generate or fill out paperwork like a description for a job posting – while the AI system may make a handful of grammatical or content mistakes, it could ultimately can save hours of work in the long run, as long as there is a human in the loop checking its work. As long as end users have an understanding of their limitations, even imperfect AI applications working in concert with humans can be tremendously useful.

Thus far, much of the CDAO’s work has helped set a theoretical foundation for AI adoption in the DoD by laying out the DoD’s strategy for a data mesh and responsible AI adoption. Going forward, the CDAO should focus its attention on the highest impact gains—connecting specific end users with relevant AI technology. The CDAO should work closely with the Services and COCOMs to refine and strengthen programs like the ADA teams in order to identify precise challenges and end users who stand to gain from AI integration.

So what does all of this mean for startups who hope to sell AI-enabled products to the DoD?17

While the CDAO is a good place for startups to get a sense of the DoD’s priorities in AI, ultimately, it will be crucial for startups to connect directly with end users and program offices to understand how their products can solve real problems. Startups should first look to work with stakeholders like the COCOM’s ADA teams and chief data officers who have a deep understanding of both the problems faced by end users and how new technology can be used to solve those problems. Then, once startups are sure they have a product that serves real end user needs, startups should connect with program champions within the Services’ program offices, as the majority of the DoD’s budget resides within these program offices. No matter how good a product is, typically, the DoD’s end users do not have the authority to buy products at scale, so startups must find the right stakeholders in program offices who have issued requirements and have budget and acquisition authority.

Going forward, CDAO should continue to strengthen its relationship with the Services and COCOMs and develop ways to connect technology providers with end users who will benefit from AI adoption. In particular, the CDAO should start by encouraging the Services to adopt AI to tackle “low hanging fruit” like using generative AI for managing the DoD’s massive amount of paperwork. Startups should focus on problem statements for the Indo-Pacific where there will be significant budget dollars in operations and maintenance (O&M) spend from INDOPACOM in years to come. Additionally, startups should look for RDT&E18 funding from organizations like the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), which will likely have a $983M budget in FY 2025 (a more than $800M increase from its FY 2024 budget which includes line items for AI technologies like AI development tools, AI for ISR drones, AI for ISR data and analytics, and AI for cybersecurity testing). While the CDAO will guide the DoD as it accelerates its AI adoption, startups will want to focus their efforts on units at INDOPACOM, DIU, and other units with budget to spend now where AI can be a game change in improving warfighter capabilities.

As always, please do not hesitate to reach out if you or anyone you know is building AI-enabled products at the intersection of national security and commercial technologies! And please let me know your thoughts – I know this is a quickly changing technology space and welcome any and all feedback. Where else are there opportunities for advancements in AI and ML to revolutionize national security? How else can the US DoD and CDAO best advance the adoption of AI?

Note: The opinions and views expressed in this article are solely my own and do not reflect the views, policies, or position of my employer or any other organization or individual with which I am affiliated.

However, I will note that military analysts believe that Russia’s military AI adoption has slowed as a result of the war in Ukraine and sanctions imposed on Russia. For more, see this Center for New American Security (CNAS) report on the subject: “Russia’s Artificial Intelligence Boom May Not Survive the War”.

Namely the DoD Chief Data Officer, the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC), the Defense Digital Service (DDS), the Advancing Analytics (Advana), and the Project Maven teams.

CJADC2 stands for “Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control” and is a DoD-wide initiative designed to improve the integration and interoperability of U.S. military forces across all domains and services. The goal is to provide a unified, cohesive approach to military operations, enabling faster and more efficient decision-making and response times. For more, see the DoD’s Summary of the Joint All-Domain Command and Control Strategy.

For a concrete example of how UDL is used by the F-35 program, see this press release: Space Systems Command’s Unified Data Library participates in Army's Project Convergence

APIs act as “bridges” between different software applications, enabling them to interact and share functions and data in a structured and secure way, without needing to know how the other system works internally.

It is important to note that the DoD rarely buys standalone products like Databricks. Typically, the DoD will hire a contractor like Booz Allen who will then purchase and implement a product like Databricks for the DoD.

Despite Google employees’ outcry a few years ago, a number of commercial companies continue to contribute to Project Maven including Palantir Technologies, Amazon Web Services, ECS Federal, L3Harris Technologies, Maxar Technologies, Microsoft and Sierra Nevada. Project Maven is composed of several different initiatives.

For a good overview of Project Maven’s computer vision capabilities, see this Bloomberg article: “AI Warfare is Already Here”

NGA took over responsibility for geospatial intelligence analysis in early 2023. For more on the geospatial intelligence capabilities of Project Maven, see this talk given by the Associate Director of the NGA

For more on CDAO GIDE exercises and AI battle labs, see this Defense Innovation Board report: “Building a DoD Data Economy”

To be precise, in FY 2025 the CDAO has about $658M to spend on development, experimentation, and demonstration capabilities.

COCOMs are joint military commands in the United States Department of Defense that are composed of forces from at least two military services. They are established to provide effective command and control of U.S. military forces across various geographical areas or for specific functional missions. Examples include INDOPACOM (responsible for Indo-Pacific region), EUCOM (responsible for Europe), and CYBERCOM (responsible for cyber operations).

SOCOM = Special Operations Command

The CDAO has been tight-lipped about particular projects ADA teams have worked on. However, the authors of the DIB report I referenced earlier had the opportunity to speak with ADA teams and were able to report on their mixed results.

Sometimes referred to as Chief Data and Analytics Officers or Chief Data and AI Officers.

RDT&E = Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation